Trust your gut ? Science says you should !

After many years of research, there is evidence to show that microbiota impacts not just physical health, but also emotional well-being in humans.

Here’s a glimpse of the journey so far…

Rodent models have demonstrated the effects of gut microbiota on emotional and social behaviors.

Stephen Collins, a gastroenterology researcher at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, has found that strains of two bacteria, lactobacillus and bifidobacterium, reduce anxiety-like behavior in mice. These bacteria strains are also found in humans. In one study, Collins’s team, collected gut bacteria from a strain of mice prone to anxious behavior, and then transplanted these microbes into another strain inclined to be calm. The result: The tranquil animals appeared to become anxious.

Most of the research so far has been done in mice, so researchers are cautious to avoid overhyping the results and what it means for people. The mice most often used in these studies are germ-free, having been bred in sterile conditions so they have no microbes living in their intestines (the typical human gut has trillions of bacteria and other microorganisms). This allows researchers to examine how the absence of gut bacteria, or the selective dosing of mice with specific bacteria, affects the brains and ‘mental health’ of mice, something not possible in people.

A paper published in the May 2015 issue of Psychopharmacology by the Oxford University neurobiologist Phil Burnet looked at whether a prebiotic (a group of carbohydrates that provide sustenance for gut bacteria) affected stress levels among a group of 45 healthy volunteers. Some subjects were fed 5.5 grams of a powdered carbohydrate known as galactooligosaccharide or GOS, while others were given a placebo. Previous studies in mice by the same scientists had shown that this carb fostered growth of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria; the mice with more of these microbes also had increased levels of several neurotransmitters that affect anxiety, including one called brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

In this experiment, subjects who ingested GOS showed lower levels of a key stress hormone, cortisol, and in a test involving a series of words flashed quickly on a screen, the GOS group also focused more on positive information and less on negative. This test is often used to measure levels of anxiety and depression, since in these conditions anxious and depressed patients often focus inordinately on the threatening or negative stimuli. The results are similar to those seen when subjects take antidepressants or anti-anxiety medications.

Yogurt is the new apple

Perhaps the most well-known human study was done by Mayer, a UCLA researcher. He recruited 25 subjects, all healthy women; for four weeks, 12 of them ate a cup of commercially available yogurt twice a day, while the rest didn’t. Yogurt is a probiotic, meaning it contains live bacteria, in this case strains of four species: bifidobacterium, streptococcus, lactococcus, and lactobacillus. Before and after the study, subjects were given brain scans to gauge their response to a series of images of facial expressions—happiness, sadness, anger, and so on.

To Mayer’s surprise, the yogurt eaters showed calmer reactions to the images than the control group. The bacteria in the yogurt changed the makeup of the subjects’ gut microbes, and that this led to the production of compounds that modified brain chemistry. The results are published in the journal of Gastroenterology (2013)

Mood altering bugs

A new study led by the University of California Los Angeles appears to have found evidence of yet another unusual link between your stomach and your brain. Namely, a selection of gut microbes seem to be linked to regions of the brain associated with mood and general behavior, the first time such a mechanism has been found in healthy humans.

Bugs and Brain- The Mysterious Interconnection

It’s not yet clear how the microbiome alters the brain. Most researchers agree that microbes probably influence the brain via multiple mechanisms:

- Scientists have found that gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine and GABA, all of which play a key role in mood (many antidepressants increase levels of these same compounds).

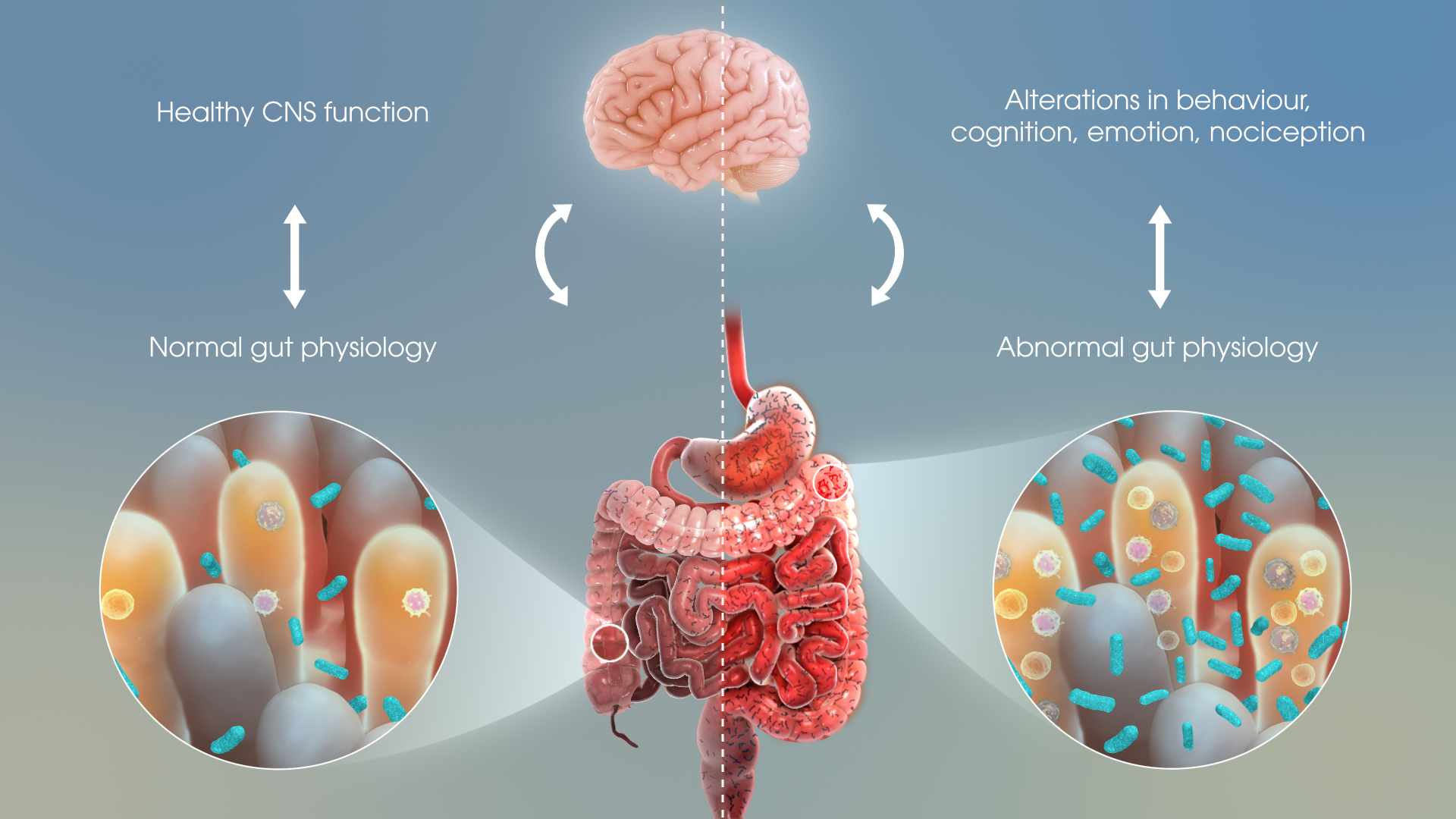

- The brain-gut axis is a bidirectional communication system between the CNS and the GI tract and serotonin functions as a key neurotransmitter at both terminals of this network.

- Certain organisms also affect how people metabolize these compounds, effectively regulating the amount that circulates in the blood and brain. Gut bacteria may also generate other neuroactive chemicals like butyrate, that have been linked to reduced anxiety and depression.

- Cryan and others have also shown that some microbes can activate the vagus nerve, the main line of communication between the gut and the brain. In addition, the microbiome is intertwined with the immune system, which itself influences mood and behavior.

A far more diverse population may come up with very different results. The prevalence of Prevotella, for example, varies wildly in the gut microbiomes of, say, European and African children. But notwithstanding ethnic differences, the connection and influence of the gut biome on mood, perception and humor seems undeniable.