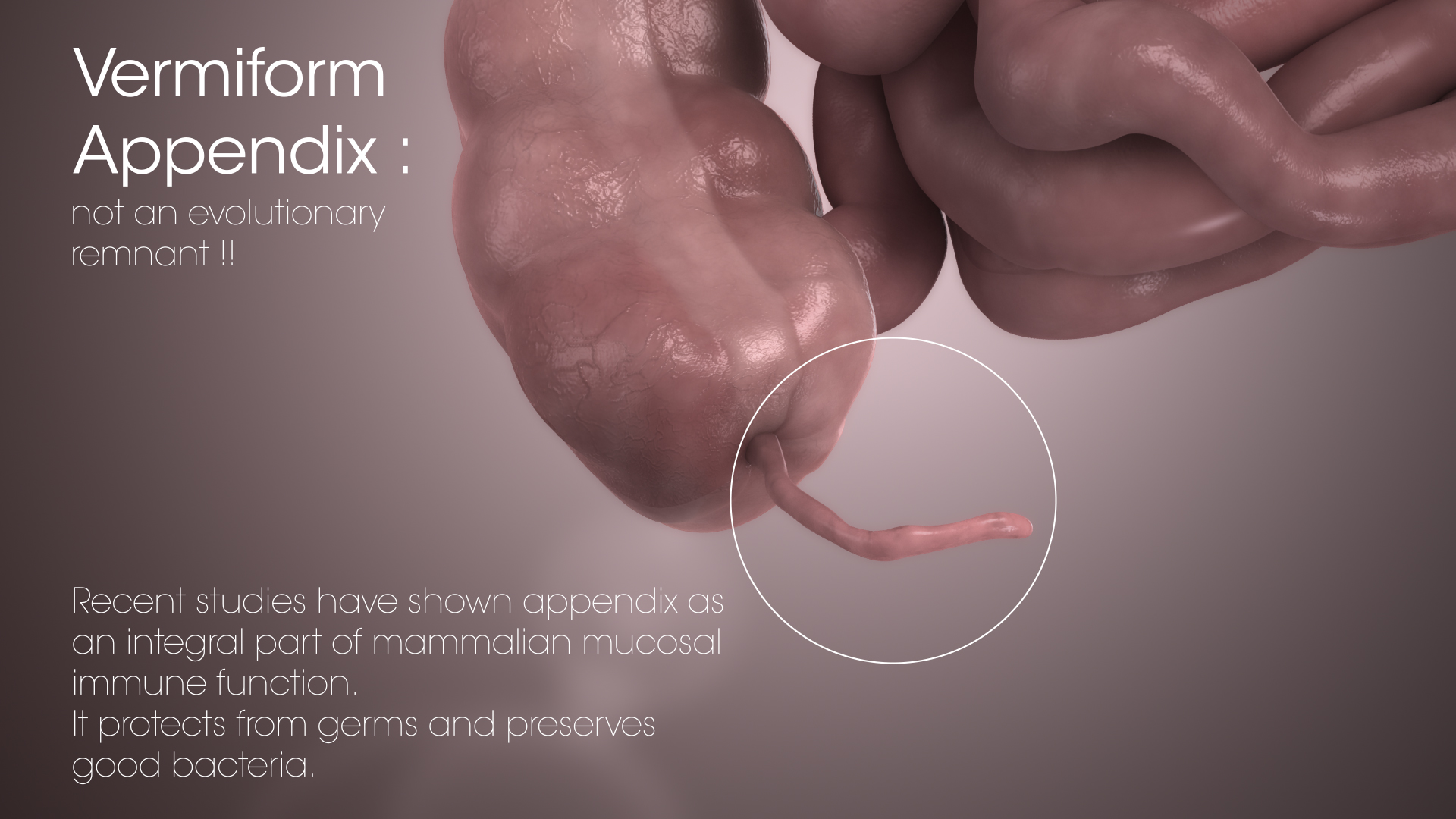

The human appendix, a slimy sac that hangs between the small and large intestine, has always been known as an evolutionary artifact that serves no purpose, but can potentially become a lethal case of inflammation. CDC reports 320,000 people are hospitalized each year and upto 400 Americans die due to appendicitis.

However, recent research studies have suggested that it is a lot more than a just a useless remnant sitting in the abdomen.

Researchers from Midwestern University traced the appearance, disappearance, and reemergence of the appendix in several mammal lineages over the past 11 million years, to figure out how many times it was cut and brought back due to evolutionary pressures.

They found that the organ has evolved at least 29 times - possibly as many as 41 times - throughout mammalian evolution, and has only been lost a maximum of 12 times.

Had the appendix been a vestigial organ, what could be the reason for its multiple comebacks in humans and other mammals across millions of years?

The usual location of appendix is in the lower right side of the abdomen but, in rare cases, it may also be located on the left side (situs inversus).

As indicated by the above numbers, appearance of the appendix is significantly more probable than its loss. Thus, the hypothesis that the appendix has a little adaptive value or function among mammals, can likely be rejected.

The reason it still exists is because it’s too ‘evolutionary expensive’ to lose.

Simply put, for the human species to gradually lose the appendix through thousands of years of evolution, it needs to be causing trouble to everyone, and to be of little use otherwise. But that’s not the case. In fact, it is likely not just dormant in the body.

Some surprising functions of vermiform appendix might be:

-

Probiotic storage

When someone suffers from diarrhea, cholera or dysentery, the good bacteria in the colon die rapidly. That’s when the appendix apparently steps up to help recolonize the gut with good bacteria. It functions as a vital safe house for good bacteria till they are needed to populate the gut. .

Consequently, as per this hypothesis, individuals with an intact appendix should be more likely to recover from gut infections than those without. To test this prediction, James Grendell, chief of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition division at Winthrop University Hospital, studied a pathogen Clostridium difficile or “C.diff”. C.diff is a deadly pathogen often encountered in hospitals, particularly when patients must be treated by prolonged courses of antibiotics.

C.diff, apparently, is not competitive with the native gut biota, but when the native biota is depleted after several courses of antibiotic treatment, and the immune cells are at their weakest, it may grow quickly and takes over. That’s when it is most dangerous for the human body.

To compare whether individuals without appendix were at a higher risk of recurrence from C.diff. and whether the risk of recurrence varied as a function of whether patients were younger or above 60, Grendell and his team worked with 254 patients who were above 18 years of age and had a history of C.diff infection. The team then focussed on the subset of patients for whom the presence and absence of an appendix was known.

The results made 2 things clear:

- Patients older than 60 were more likely to have recurrences of C.diff, independent of any other factors.

-

Individuals without an appendix were 4 times more likely to have a recurrence of C.diff. Recurrence in individuals with their appendix intact occured in 11% of cases, while recurrence in individuals without appendix occurred in 48% of cases.

Studies on animal species have also revealed that those with a tapering or spiral-shaped cecum were more likely to have an appendix than their counterparts with a round or cylindrical cecum. This suggests that the appendix may be evolving as part of a larger "ceco-appendicular complex" including both the appendix and cecum.

-

Lymphatic system component

Another significant observation was that the species with an appendix had higher average concentrations of lymphoid tissue in the cecum. This finding suggests that the appendix may play an important role as a secondary immune organ. Lymphatic tissue can also stimulate growth of beneficial gut bacteria. So it may be that the appendix helps in the synthesis, direction and training of WBCs.

-

Fetal role

Loren G. Martin, professor of physiology at Oklahoma State University, has quoted- “The appendix serves an important role in the fetus and in young adults. Endocrine cells appear in the appendix of the human fetus at around the 11th week of development that have been shown to produce various biogenic amines and peptide hormones, compounds that assist with homeostatic mechanisms.”

-

Non-evolutionary uses

Professor Martin also added, "In the past, the appendix was often routinely removed and discarded during other abdominal surgeries to prevent any possibility of a later attack of appendicitis; the appendix is now spared in case it is needed later for reconstructive surgery if the urinary bladder is removed. In such surgery, a section of the intestine is formed into a replacement bladder, and the appendix is used to re-create a 'sphincter muscle' so that the patient remains capable of retaining urine. In addition, the appendix has been successfully fashioned into a makeshift replacement for a diseased ureter, allowing urine to flow from the kidneys to the bladder. As a result, the appendix, once regarded as a nonfunctional tissue, is now regarded as an important 'backup' that can be used in a variety of reconstructive surgical techniques.”

It would, therefore, be correct to say that human appendix has saved more lives than it has taken.

References: