A new study of an astronaut and his identical twin is informing the nature vs. nurture debate, especially in the context of space travel

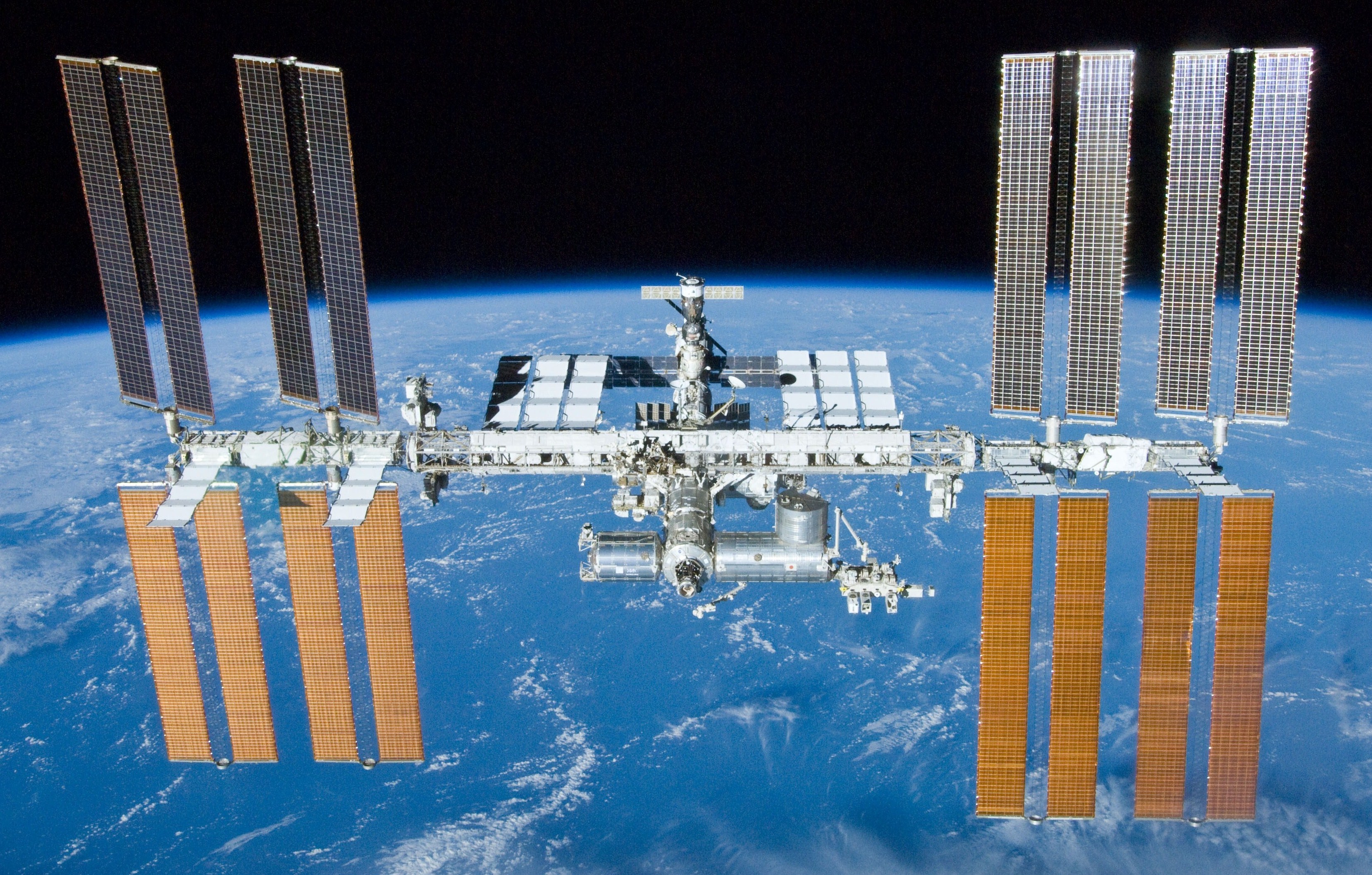

Going to Mars is riddled with both technical hurdles and also with very human ones. How will the human body adapt to long space trips, or the mind to long periods of isolation, and could changes be permanent. NASA Astronaut Scott Kelly’s recent year-long trip to the International Space Station achieved both a new milestone in long-duration space travel, but also offered unique insight into the effects of space travel on human biology. Especially since Kelly had a natural DNA control for the experiment – his identical twin!

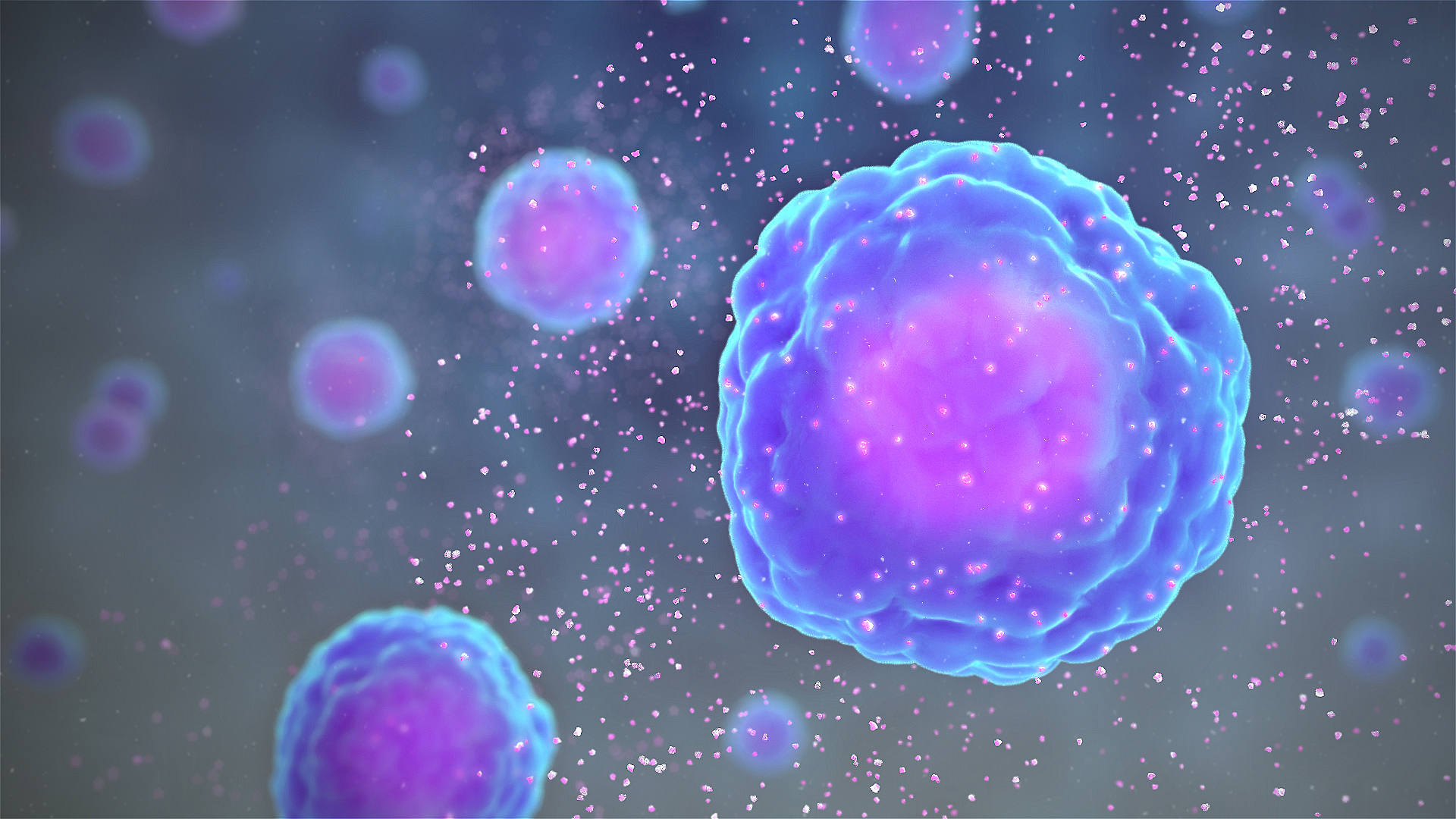

NASA’s findings from Kelly’s mission reveal some understandable and yet startling changes to Kelly’s biology. Kelly’s body predictably adapted to the rigors of space travel, which are much like SCUBA diving, mountain climbing or any other form of hypoxia (sustained oxygen deprivation). Hypoxia is a serious concern, and has been linked with diseases including diabetes, Alzheimer’s and cancer. The lack of oxygen hampers mitochondrial function. Mitochondria, the “power plants” of the body, make energy proteins called ATP. But mitochondria do adapt to sustained hypoxia, for example by generating HIF-1 factor. So it is key to understand how long-term, space-induced hypoxia affects biology. Kelly’s post-mission blood tests indicate likely hypoxic damage to mitochondria by showing a compensatory increase in mitochondria levels.

Besides metabolism, NASA found that the radical change in environment caused an immune response. Normally, the immune system responds to infection, wounds, or the presence of foreign bodies, but NASA found that Kelly’s immune system was hyperactive, possibly without any of the normal expected triggers. Changes also extended to blood clotting, bone formation, and collagen. Some of these changes and responses are most likely due to body fluid shifting upwards in zero-gravity. Fluid shifting can increase inter-cranial pressure and induce vision changes.

While understanding hypoxic and zero-G changes are very important for attempting a mission to Mars, the data from Kelly’s mission are valuable, but not unexpected. The surprise is that Kelly’s genes now express differently than his identical twin. The shift is not pronounced, only about 7%. But even after two-years, some of Kelly’s gene expression has not reverted, indicating that some changes are likely permanent. For example, while in space, Kelly’s telomeres – the end regions of chromosomes, increase in length, a sign of de-ageing. But within 48 hours of landing on Earth, they reverted to almost pre-flight levels. Now, this could have less to do with space, and more to do with the calorie-restricted diet that Kelly followed on his mission, but either way the future of space travel will have to account for genomics.

Therefore, the twin studies act as a marker that heralds a new era in genetics; namely, the genomics of space travel.