Most of us have witnessed the development of head-mounted display (HMD) products and how they’ve contributed to an incredible hype around mass-market virtual reality.

The technology has advanced to the point where high-quality VR experiences are possible. Among the industries that have been basking in the light of profound advances of VR technology, Healthcare is one.

But as sophisticated as VR has become, it still may not be ready for prime time. Not only because the devices are costly, complicated and unwieldy, but because of the health risks they pose both to the physical and emotional well-being.

There has been an irking oversight on the health and safety threats associated with strapping a big plastic block over the eyes, which, if not properly addressed, could prove to be a disaster.

The concern of VR’s impact isn’t just limited to the physical health but also extends to human behavior. As Albert “Skip” Rizzo, director for medical virtual reality at the University of Southern California pointed out “Psychology as a science has been around for 100 years studying how humans behave and interact in the real world. I think we need almost as much time now to study how humans behave and interact in the virtual world and what those implications are.”

Can our bodies and minds cope with VR?

Oculus’ risk and safety guide lists these as potential symptoms

- Fatigue

- Loss of awareness

- Eye strain

- Involuntary movements

- Dizziness

- Disorientation

- Nausea

- Impaired hand-eye coordination

- Excessive sweating

- Seizures

- Eye or muscle twitching

- Increased salivation

- Lightheadedness

- Altered, blurred, or double vision or other visual abnormalities

- Discomfort or pain in the head or eyes

- Drowsiness

- Impaired balance

The Wall Street Journal recently laid out some of the health warnings that come with the current generation of VR technology:

“The experience can cause nausea, eyestrain and headaches. Headset makers don’t recommend their devices for children. Samsung and Oculus urge adults to take at least 10-minute breaks every half-hour, and they warn against driving, riding a bike or operating machinery if the user feels odd after a session.”

Where are these claims coming from?

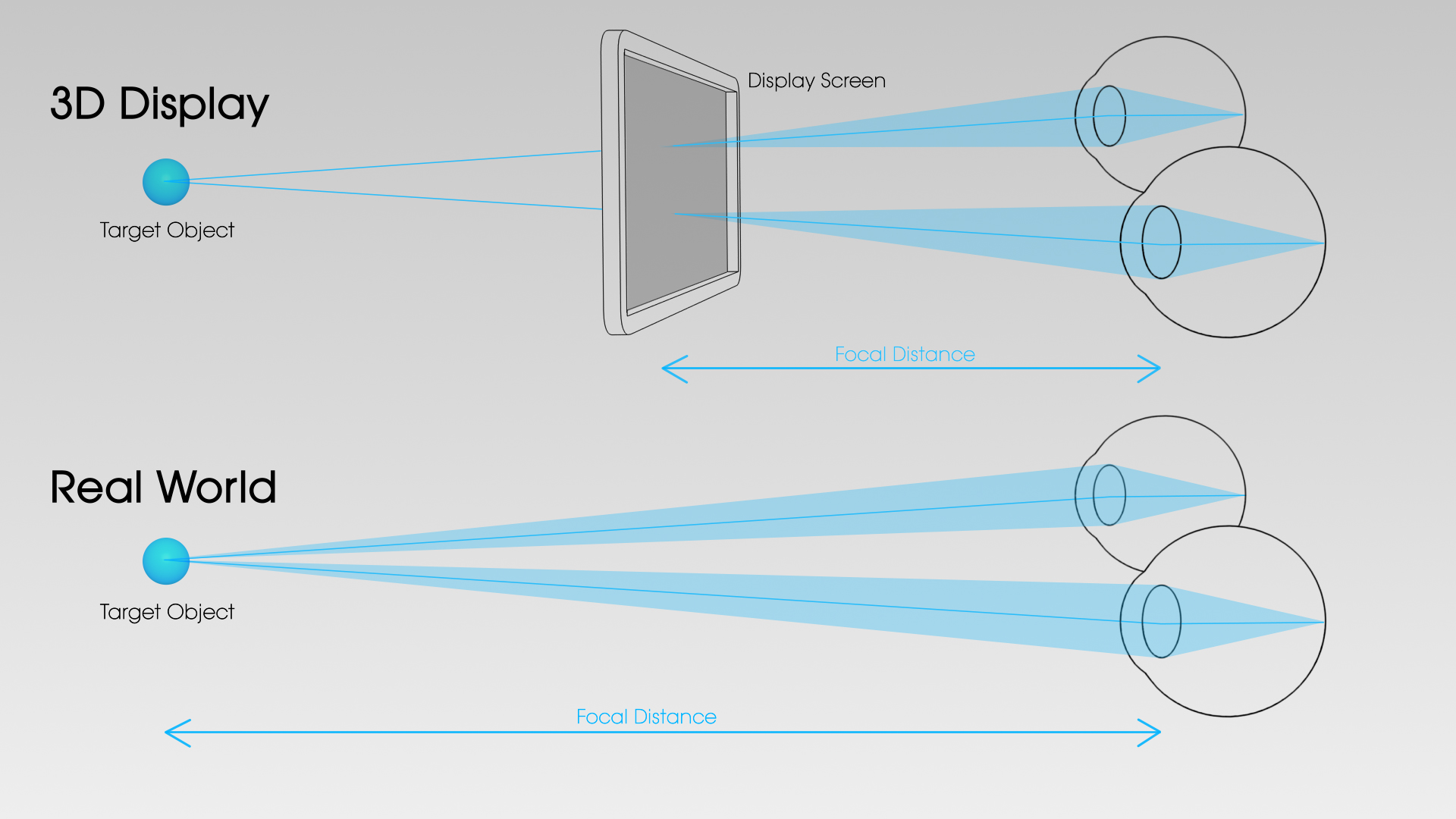

Viewing an object involves two basic things. First is vergence. Under this our eyeballs point towards that object. If the object is close, the eyes naturally converge on it; if it’s far, they diverge. If our eyes don’t line up correctly, we end up seeing double.

The second thing that happens is accommodation, i.e., the lens inside the eye adjusts to bring the object in focus. To view real objects of nature, vergence and accommodation are coupled as they’re both trying to get to the same distance.

However, the stereoscopic VR headsets create 3D images by showing offset images to the left and right eye. The more offset, the closer an object appears, which means that the eyes are constantly accommodating to the screen, but they’re converging to a distance further off. This vergence-accommodation conflict makes them tired and sometimes, even rebellious.

The mismatch between what you see and what you feel causes the stomach to churn and contributes to sickness. The sickness is a consequence of “vestibular and visual mismatch” or the conflict between the stimuli the eyes send to the brain and the stimuli the inner ear sends to the brain.

Further, eyes are strained when they are made to focus on a pixelated screen that uses a single refractive optic element which is unable to adequately address the optic issues with near-to-eye devices.

However, what Virtual Reality does to our minds rather than our bodies, is a bigger issue.

Human brain is highly neuroplastic; the near-eye stereoscopic 3D systems can potentially cause neurologic changes in it.

Professor Mayank Mehta and his colleagues at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) have been conducting experiments to explore the effects of VR on the brains of rats. They particularly monitored the activity in the hippocampal region (an area of the brain important for spatial awareness, learning, and memory).

Although there are no concrete conclusions, experiments on rodents show VR activates less neurons than reality does; 60 percent of neurons simply shut down in virtual reality environments.

Apart from the health concerns, a very valid concern associated with virtual reality is if it’s the next level of isolation. As people become more reliant on virtual interaction over time, the lack of human interaction can strain vital relationships (with friends and family) and eventually the absence of physical communication. This could be a potential cause of illnesses like depression.

Moreover, world away (and mostly in stark contrast) from the real world is likely to encourage escapism. People may ignore their real life problems and forget important responsibilities by taking refuge in the virtual world. This could cause them to face irreparable damage in the long run.

Also, being strapped into a fully occluded device cuts one from their surroundings, creating obvious physical dangers.

So If you're an early adopter, take the full-motion VR hardware seriously.